The AI Overreach Problem: When Design Forgets the User

Why AI’s aggressive integration is breaking user experience and product trust

When Products Forget Their Purpose

Last week, my parents opened Microsoft Word, expecting the familiar blank page—the starting point for countless letters, documents, and stories.

Instead, they were met with a prompt:

"Let Copilot help you draft."

No explanation, no context—just an invitation for the software to assist them in writing before they had even gathered their thoughts.

"What's Copilot?" they asked, confused.

A word processor’s job description is simple: help people process words. Not generate them. Not predict them. Not replace them. Process them.

Yet here was Word—software that had faithfully served many writers for decades—eager to insert it’s shiny new capability before my parents had even begun to write a word.

This isn’t just feature creep—it’s a crisis of product identity. In the rush to integrate AI, we’re undermining the very purpose of the tools we create. We’re not enhancing products—we’re fundamentally changing them.

The blank page—a timeless and universal symbol of possibility—is no longer blank. The space where creativity begins now imposes algorithmic influence before fingers even touch the keyboard.

And it’s not just Word. Across the industry, AI integrations are breaking fundamental design principles, shifting tools away from their original purpose, and alienating users.

As the legendary Don Norman wrote:

"Good design is actually a lot harder to notice than poor design in part because good designs fit our needs so well that the design is invisible, serving us without drawing attention to itself."

AI should be invisible when it needs to be. Instead, it's taking center stage—whether we asked for it or not.

The Promise of Purpose

Great products keep their promises. They create a consistent, predictable experience that users trust.

A word processor promises to help you refine your thoughts, just as a notebook promises to capture them. Every tool establishes an unspoken contract with the user—a clear understanding of how it will serve them, and just as importantly, when it will step aside.

But when a product breaks that promise, it forces users into an experience they never agreed to. Generative AI in a word processor doesn’t just add functionality—it reshapes the entire interaction. The product itself changes, and so does the way users engage with it.

What was once a blank page—a space for thought, creativity, and intent—now demands the user’s attention before they’ve even begun. Instead of writing, they’re prompted to think about prompts. Instead of forming their own ideas, they’re nudged toward curating the means for the best probabilistic guess of what they might really want to say.

The experience shifts from authorship to curation, from creation to selection—where the tool inserts itself before the user has even gathered their thoughts.

This isn’t just an evolution of software—it’s a shift in control.

A note-taking app promises to capture your ideas as they come.

A camera app promises to take a photo when you press the shutter.

A writing tool promises to help you write true to your vision.

But when AI assumes control—suggesting words before they’re thought, altering images before they’re reviewed, surfacing “smart” notes before they’re written—it disrupts the natural flow of user interaction. It redefines who is in charge.

When products break this contract, they don’t just frustrate users—they undermine trust and autonomy.

A tool that once felt intuitive and dependable now feels unpredictable, intrusive, and misaligned with the user’s intent. Instead of enabling creativity, it competes for control.

The more a tool asserts itself, the less it feels like something you use—and the more it feels like something you have to manage.

Once users lose confidence in how a product behaves, they stop trusting it. And when they stop trusting it, they stop using it.

Great design will ensure AI supports users—rather than steering them.

Generative AI Isn't New—But the Hype Is

The challenge of integrating generative AI isn’t new. What’s new is how aggressively it’s being forced into every product.

Fifteen years ago, Adobe introduced Content-Aware Fill to Photoshop CS5. Select an object, press a button, and Photoshop would seamlessly reconstruct the background as if the object had never been there. It felt like magic.

It was, fundamentally, an early form of productized generative AI—yet it never disrupted the user’s workflow.

Adobe marketed and implemented Content-Aware Fill as a means to facilitate the user’s vision—not replace it. The adjustment was made by the user, not for them.

Photoshop didn’t assume any object needed to be filled.

It didn’t interrupt your work with unsolicited suggestions.

It was there when needed—invisible when not.

Now compare that to today’s AI integrations:

Before you type a word, AI is ready to write for you.

Before you review your photos, AI is stitching them into slideshows.

Before you select a canvas size, AI is offering suggestions—shaping the work before you’ve even begun.

These tools no longer wait for user intent—they rush to fill every blank space.

When Photoshop introduced Content-Aware Fill, it was designed to extend user capabilities on demand—not dictate the workflow.

But today’s AI features lack that restraint. Instead of supporting user intent, they preempt it.

The contrast is clear:

Content-Aware Fill succeeded because it remained an option, not an imposition.

Today’s AI integrations disrupt more than they improve—demanding attention, assuming problems that don’t exist, and compromising the core experience of the tools they inhabit.

The issue isn’t AI itself but the failure to design it in service of the user and respecting their agency.

A Question of Trust

Trust isn’t built on probability. It’s built on intentional design.

When AI is embedded into core product experiences without oversight, we’re not just outsourcing design decisions and value delivery to probability models—we’re forcing users to be our quality assurance team.

Instead of delivering reliable, well-crafted tools, we’re asking users to navigate unpredictable AI-generated outputs, hoping the system gets it right. And when it doesn’t? The burden is on them to detect, correct, and adapt.

That erosion of trust is why many users, myself included, are moving away from once-reliable tools that have succumbed to this.

AI is undoubtedly a powerful tool for building the next generation of products—but right now for many products, it will be better suited for design and development than for driving the experience itself.

We have real problems to solve—bugs to fix, backlogs to clear, workflows to improve. AI can help us work faster, refine ideas, and validate solutions—but the responsibility still lies with us as makers.

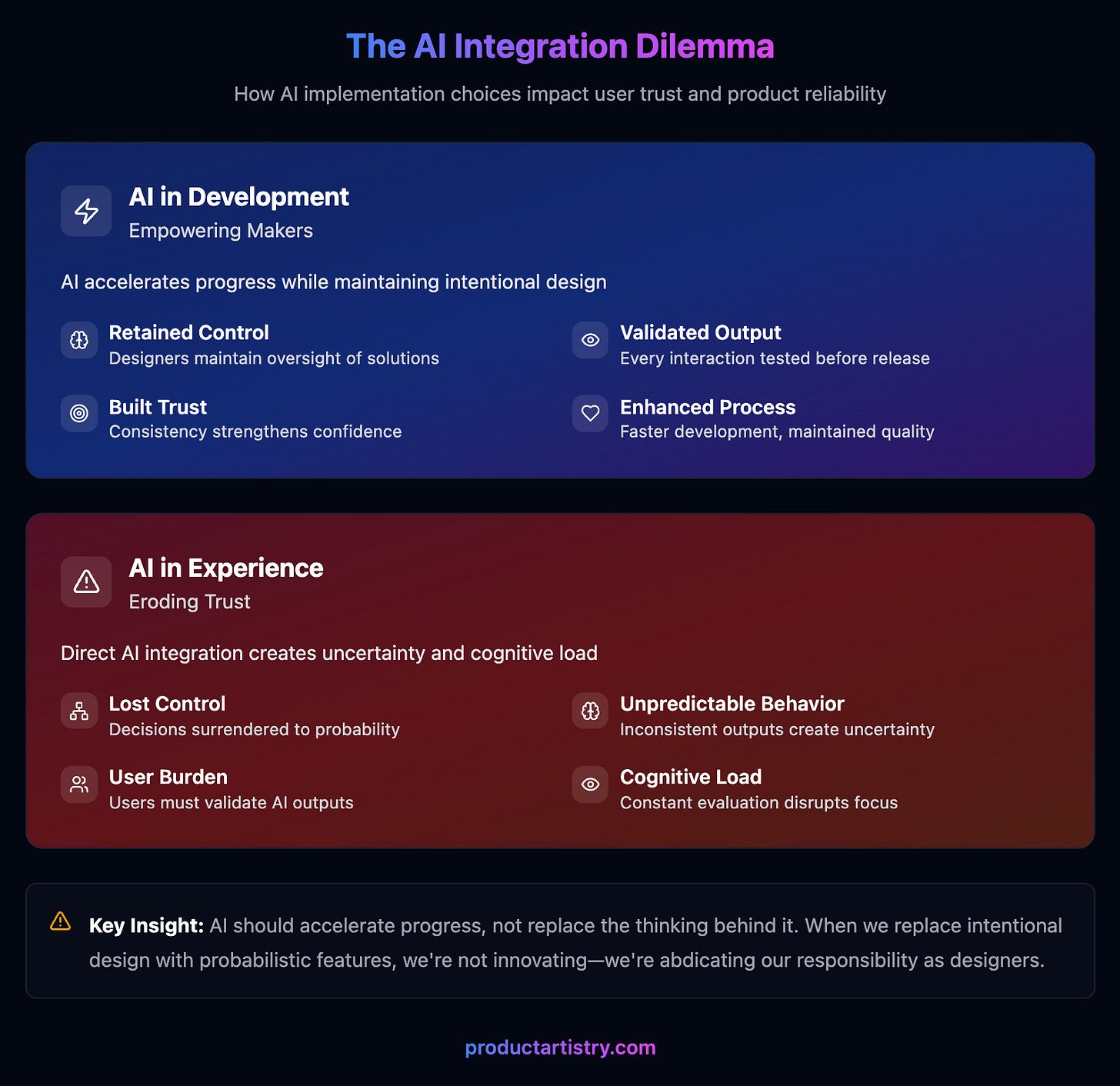

When AI is used to improve development:

Designers and engineers retain control over the final solution.

Every interaction is validated before reaching the user.

The product remains predictable and reliable.

Trust is built through consistency.

When AI becomes the product experience itself:

Control is surrendered to probability.

Behaviors become inconsistent and unpredictable.

Users must validate and correct AI-generated outputs.

Trust is replaced with hesitation.

The distinction is clear: In most cases, AI is best used to accelerate progress toward meaningful development, not to serve as the sole arbiter of a product’s features, value, or purpose.

A tool that forgets its purpose fails the people who rely on it. When a tool works well, it fades into the background, allowing users to focus on their work and enter flow. But when AI takes over core interactions, users are forced into a constant cycle of evaluation and doubt:

Is this response correct?

Should I regenerate it?

Can I trust this suggestion?

These aren’t minor inconveniences—they’re cognitive burdens that pull users away from their actual tasks. It’s the digital equivalent of a poorly designed door—where people stop, hesitate, and second-guess, unsure whether to push or pull.

When we replace intentional design with probabilistic AI features, we’re not innovating. We’re abdicating our responsibility as designers.

Choosing a Better Path

As builders and designers, we face a choice.

Before integrating AI, we should ask:

Is AI helping us build a better product, or are we using it to avoid making real design choices?

Is it reinforcing our product’s purpose, or is it steering it somewhere different?

Is it strengthening user trust, or slowly eroding it?

Is it making our product more reliable, or more unpredictable?

Great products are built through deliberate, thoughtful decisions that put users’ needs first.

AI can help us work smarter, move faster, and refine our craft—but it should never be a replacement for clear intent, accountability, and the discipline of good design.

The best products last because they serve a purpose, not a trend. In the race to innovate, we need to ask ourselves:

Are we designing with intent, or offloading the burden to AI and our users?

That choice defines everything.

Keep iterating and stay purposeful,

—Rohan

→ Connect with me on LinkedIn. Interested in working together? Here’s how I can help.

Thanks for reading! If you’ve found value in these ideas, there are three simple ways to share your support:

Like and Share: Spread these ideas to others who they may resonate with.

Subscribe for Free: Get future posts delivered straight to your inbox.

Become a Paid Subscriber: Support my work (and caffeine addiction).

Still here? I’d appreciate you taking a second to answer this quick poll for feedback:

This was a very thoughtful piece Rohan, I really enjoyed it! There are fundamental principles that Product folks should consider before integrating AI with their products before it changes the experience entirely.

Here's hoping there's a future for thoughtful AI product development.

Powerful comparison with the blank page, Rohan.

It definitely seems that, while the tech is transformative, the hype just went way overboard. Most discussions just end up being about the end of the world, or how we shouldn’t care about learning cause we can outsource our thoughts.

The sheer force with which it is being forced upon is not exactly helping the discussion, either.